I studied economics at UC Santa Cruz from 1994-1997. Actually, that’s only half true: I slept through nearly all of my economics core classes at UC Santa Cruz. My favorite example of this being Econ 1: Introductory Microeconomics taught by Nirvikar Singh.

As far as I know, Prof. Singh was a good teacher. By this, I mean that I came to understand basic economics through his class, or at least, the version taught by the textbook he used. Okay, I really don’t know whether he was a good teacher, but I heard good things about him from other students in the class.

Of the three classes I took my first semester in college, Econ 1 has turned out to be the most valuable, with second semester calculus coming in a close second. Coming in third place, is the College Eight brainwashing class, or shall I say, attempted-brainwashing class. (College Eight now goes by the name, Rachel Carson College. More on that another day though).

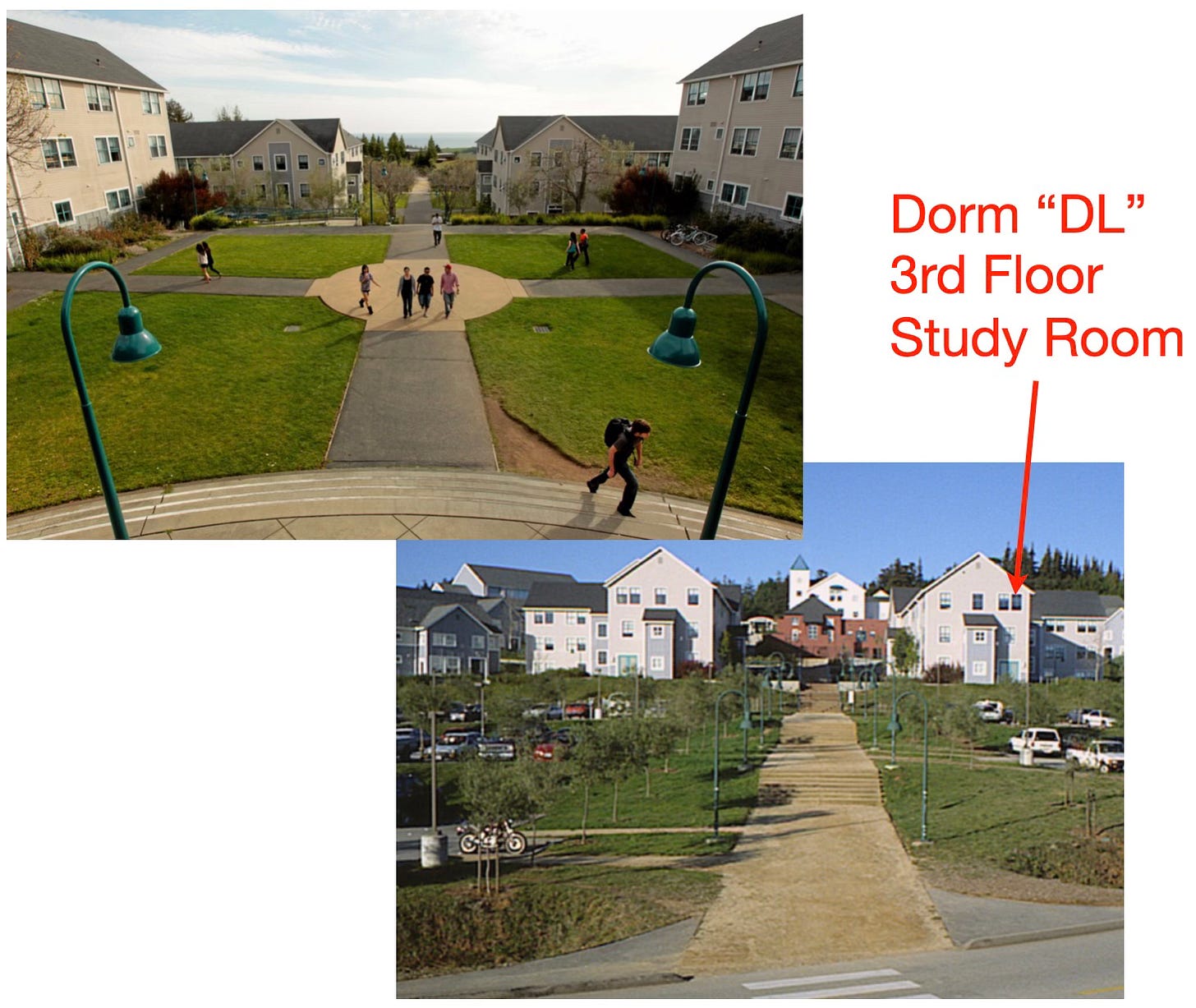

Each weekday, fall quarter of my freshman year, I would wake up on the 3rd floor of my College Eight dorm building — dorm “DL” — walk down the hallway to the communal study room; plop myself down on the carpet or a couch, crack open my Econ 1 textbook, and begin reading.

This was a bright, sunny room overlooking the Monterrey Bay and the Pacific Ocean. There I would read for an hour or two before class. I would highlight with a yellow fluorescent highlighter, sometimes nearly every sentence on a particular page.

After my morning reading, I would walk to class, through the upper part of the Great Meadow, and into the big lecture hall housing Dr. Singh’s lecture.

There I would try my best to stay awake, but nearly every single lecture, about 10 minutes into the lecture, I would pass out. I only remember a few things from that lecture room, none all that important. Besides Nirvikar’s turban, his Indian-English accent, and his overhead projector, I remember a class demonstration using a Nestle Crunch bar.

The demonstration was memorable because Prof. Singh picked a student from the classroom to participate in the demo. I didn’t know him at the time, but this student always seemed to sit next to, or near the hottest women in the class. I have no memory of what that lesson taught; all I remember is that the student got to keep the Crunch bar. Turns out that student became a good friend, and is one of my subscribers today. Maybe someday he’ll start a blog about his experiences at UC Santa Cruz.

By the end of the quarter, I had read the entire textbook cover-to-cover. Nearly every single page was highlighted in bright fluorescent yellow. On the day of the final, I was one of the first students to finish the exam, and I’m proud to say I got a 100%.

After having cheated my way into the salutatorian spot in high school, I was on the mend. Managing myself on Friday and Saturday night was a different story. Santa Cruz dorm rooms were then, and probably are now, pot-smoke filled bastions where federal drug prohibition laws don’t seem to apply. To turn down the pipe when it came your way in the circle was abnormal. “Everyone” smoked pot at UC Santa Cruz. Even the RAs.1

In fact, a few years after college, in my interview for a secret clearance while working at Lockheed Martin, I was asked, “How many times did you do it? Why’d you do it? Why did you break the law?”

My response, “Everyone did it. It was the culture of the school. If alcohol prohibition were to come back, and all your friends and family were still indulging, wouldn’t you drink with them?”

“No,” the interviewer said, “I wouldn’t break the law.” Yeah right. It appeared to me that this guy had a huge beer belly.

I signed a document that day promising I wouldn’t ever smoke pot again. And I haven’t. In fact I don’t recommend smoking pot. Sobriety is almost always superior to being drunk or high.

Anyway, that was my college introduction to economics. Today economics is foundational to my understanding of human culture. Without basic econ, my life would probably be a mess.

Starting in 2009, motivated by the passing of Obamacare I began reading econ books obsessively. My aunt, a big blogger at the time, recommended Thomas Sowell’s book, Basic Economics. In fact, just last year when asked in a job interview, what one book I would recommend that people read, I said, “Basic Economics by Thomas Sowell.” That book allowed me to read Milton Friedman’s books. From there, I found the Hoover Institute at Stanford, and Russ Roberts. Through Russ I found Cafe Hayek and Donald J. Boudreaux. From Russ and Don, I found pretty much everyone else, including Econlog, Econtalk, and George Mason University’s Mercatus Center.

Though Don Boudreaux doesn’t blog at Substack, he is a veteran daily blogger of economics, similar in output to Arnold Kling. He writes,

At the moment I have no plans to shut the blog down or to move over to Substack. Certainly the former will one day change, and maybe the latter will as well.

Prof. Boudreaux has been blogging since 2004 - for just over 20 years. Arnold Kling has been blogging since 1997!

For years I read Cafe Hayek every day. Here is a brief history of Cafe Hayek,

April 2024 – to be precise, April 13th, 2024 – marks the 20th anniversary of Cafe Hayek’s launch. Although Cafe Hayek has been exclusively my blog for several years now, it is not my brainchild. That distinction belongs to Russ Roberts, who was then my colleague in Economics at George Mason University. Russ persuaded me to join him in blogging. We pondered names for the blog. “Cafe Hayek,” the name, is also Russ’s brainchild. When the blog was launched, I was aware that I didn’t really understand what ‘blogging’ meant or entailed. But I agreed to join Russ in this endeavor because I so very much respect his judgment and intellectual entrepreneurship.

The post you’re reading now, on April 27th, 2024, is number 18,843 for me. The total number of posts at Cafe Hayek, counting this one, is 20,983. Russ’s posts, therefore, number 2,140.

Boudreaux has written 18,843 blog posts. I wonder how that compares to Kling?

So, with that introduction, let’s read some basic econ from my favorite of Don Boudreaux’s books: Globalization. This is an important passage that asks fundamental questions, like, “What causes wealth?” And, "What is wealth?” Notice that it doesn’t ask, “What causes poverty?”

Modern economics traces its origins to a book we mentioned in Chapter 1: Adam Smith's An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, first published in 1776. Note the title carefully. Smith asked what is wealth and what causes it.

Because we examined this question in some detail in Chapter 2, we need not spend much time here on what is wealth. We note straightforwardly that wealth is ready access to goods and services that make human life fuller and more enjoyable. By "wealth" we do not mean only, or even mainly, luxury goods such as diamond rings, private jets, and summer homes on Cape Cod. We mean chiefly a steady supply of food and water; solid, secure, and sanitary housing; several changes of clean clothing; decent and science-based health care; enough leisure to pursue enriching hobbies; and several years of education for every child.

Of course, as we saw in Chapter 2, most modern Americans have these things plus much more things such as automobiles, televisions, cell phones, MP3 players, personal computers, tickets to San Francisco Giants baseball games, aspirin, weekly magazines. The list is quite long. The point here is that by "wealth" we mean neither large bank accounts nor goods and services regarded today as luxuries available only to a relatively few persons.

A far more interesting question is what causes this wealth.

Before we explore the answer to this question, it's interesting to notice that Smith did not ask "what causes poverty." Smith would have found such a question to be odd, if not downright meaningless. In Smith's time, even in relatively prosperous western Europe, poverty was widespread. Poverty was the norm. Smith understood that poverty has no causes; it is (to use a modern term) humankind's default mode. If each of us does nothing, if each of us exerts no creativity and no effort, we will all be miserably poor. It is no challenge to "create" poverty.

The real challenge, Smith realized, is to create wealth, especially enough wealth so that it is regularly available to ordinary people.

Smith saw that wealth is rooted in specialization, what he called "the division of labour." As the shirt example in Chapter 1 makes clear, if each of us must produce everything that we consume, with no help from others, we would be unimaginably poor. (Actually, most of us would never have been born.) By specializing and then trading, we are all made much wealthier. The total amount of output that society produces with specialization is extraordinarily greater than the total amount that could be produced without specialization, even if everyone were to work the same number of hours.

But why? How does specialization cause such awesome increases in total output?

Adam Smith identified three reasons. First, specialization reduces the time spent moving from job to job. Someone who tends crops in the morning and then cleans skyscraper windows in the afternoon must spend a good deal of time each day traveling from the farm to the city and back. This time spent moving from one job to the next is time not spent producing output. So if Sam specializes in producing nothing but wheat and Suzy specializes in doing nothing but cleaning windows, together they'll produce more output than they would if each worked at both tasks.

Second, specialization promotes the acquisition of skills; it promotes what Smith called "the increase of dexterity in every particular workman." If each day you spend only five minutes practicing the piano, you will never be a good piano player. This is true even if you are blessed with vast natural talent for that musical instrument. To become highly skilled, each week you must play the piano for many hours. And the more time you devote to playing the piano, the better you become at it. Put differently, the less time you must spend doing other things growing your food, making your clothes, mowing the lawn, practicing karate — the more time you can spend honing your skills as a pianist and thus the better you become at making music with that instrument.

What's true for piano playing is true for nearly every other endeavor. Persons who become skilled automobile mechanics achieve this distinction only by devoting a good portion of their time each week to repairing cars and trucks. Bakers spend much time baking. Neurosurgeons spend much time learning and practicing brain surgery. Practice and experience may not make someone perfect, but they sure do improve that person's skills.

Third, specialization increases the likelihood of machinery replacing human labor and, thereby, releasing that labor to produce outputs that could not before be produced. Suppose you visit a factory and see each worker performing all the tasks required to produce a pin. Each worker pulls some wire from a roll, cuts it, sharpens one end to a point and flattens the other end to make the pin's head. Each worker also packs the pins he or she makes into packing crates for shipment to market. If the factory owner asks you, "Hey, do you think you can make a machine to do what one of these workers does?" how will you answer? You would have to be an exceptional genius of an engineer to design and manufacture a single machine that does several very different tasks.

But now suppose that you visit another pin factory, one that has the same number of workers as the first factory. In this second factory, however, one worker specializes in pulling the wire from the spool; a second worker specializes in cutting the wire; a third worker specializes in sharpening one end of each piece of cut wire into a pin point; a fourth worker specializes in fattening the other ends of the pins into pinheads; and so on. If the owner of this second factory asks you to make a machine to do one of these tasks, you are more likely to agree that designing and manufacturing such a machine is do-able. A machine that does nothing but, say, cut wire into pin-length strips is vastly easier to conceive and to build than is a machine that does this task phas many others.

So, Adam Smith reasoned, when a worker specializes in performing a distinct task, changes increase that this worker, or someone observing him perceive an opportunity for inventing a machine to do this specific task. With a machine now doing a task that previously required human labor, workers who once performed this task can now perform other productive tasks. Society gets more output than before.

Smith concluded that the wealth of nations grows with the division of labor and with the trade that naturally follows from it. As each of us specializes in doing a small, distinct job — teaching economics, preparing income-tax returns, performing dentistry, playing French horn for the New York Philharmonic orchestra — and then exchanging our output for that of millions of other specialists, we are all better off.

As summarized by the Nobel laureate economist James Buchanan and his co-author Yong Yoon:

The Smithian logic is straightforward. Why do persons trade with one another? They do so because specialization is productive; people can produce more economic value if each person does one thing instead of trying to do everything. Concentration of productive effort on one good followed by exchange for other goods becomes a means of getting more of all goods than can possibly be attained in autarky. Trading is, quite simply, a more efficient means of producing?

Smith's explanation for the wealth-producing effects of specialization is important. But it was left to a younger British economist, David Ricardo (1772-1823), to discover and explain another, more fundamental reason why specialization increases the wealth of nations. That reason is the principle of comparative advantage, and it is one of the most important discoveries in all of the social sciences.

Let’s condense this down. What causes wealth?

Smith saw that wealth is rooted in specialization, what he called "the division of labour.”

By specializing and then trading, we are all made much wealthier. The total amount of output that society produces with specialization is extraordinarily greater than the total amount that could be produced without specialization, even if everyone were to work the same number of hours.

But why? How does specialization cause such awesome increases in total output?

Adam Smith identified three reasons.

First, specialization reduces the time spent moving from job to job.

Second, specialization promotes the acquisition of skills.

Third, specialization increases the likelihood of machinery replacing human labor and, thereby, releasing that labor to produce outputs that could not before be produced.

There is nothing “special” or complicated about any of this. Hunter-gathers of 10,000 years ago almost certainly practiced these simple specialization techniques as they went about their daily lives. Likely did farmers in Mesopatomia. And surely my father did as an a business owner of an orthodontics practice in South Lake Tahoe. Regarding his 1979 BMW 735, I once asked him, “Why don’t you change your own oil?”

His answer taught me about comparative advantage. Let’s read about that next time.

Mix in a 40 oz of malt liquor, a few other students, a deck of cards and you have yourself a party — and a reason to sleep through lecture. If my kids are reading this, do not do this. I “wasted” so much time, and years later I came to regret all my drunken and sometimes stoned memories. In retrospect my memories of these inebriated activities seem dull and grey. I now much prefer the purity and clarity of sober memories. And there are many other reasons not to drink or do drugs. Having pure memories is just one of them.

You would get a kick from reading about Industrial Engineering, specifically the parts which relate to ratings and method study. This also explains a basic fallacy with regard to Americas apparent Job Vacancies- Amazon, for example, is in the habit of listing a huge number of vacancies at the same time that a particular regional centre has reduced headcount. That's because most American corporates are no longer looking for workers, but rather they are only looking for the right workers for the right jobs.

This is a problem with most Western employment markets- the incentives don't stretch far enough down, to the shop floor level. A worker who is reasonable fit, and performs at the top of the ratings performance curve, is innately valuable- and, provided that good method study and high morale systems are employed, can easily outperform the median worker by a factor of four, in terms of productivity.

Most employers realise this, but don't want to pay for it. The amount of profit which is extracted from the labour of a median basic skilled worker is a pittance, whilst the amount of profit extracted from workers in the top 10% of the ratings curve can be quite substantial indeed- at least at scale. It's also true, at least from my experience, that high ratings workers tend to be less prone to workplace accidents and possess fitness levels which argue against long-term sickness and absence. And let's not forget the overhead reduction.

In my honest opinion, workers who fit this category should be paid around twice the basic wages. It doesn't have to be set in stone, but could be more of a sliding scale. They can perform four times the work of most people, and are saving substantial costs for their employers in other ways. It's a way for people who perhaps haven't been lucky in the distribution of heterodox natural talents and innate abilities to receive dignity and a sense of personal worth in the 21st century, and could be a major stabilising influence in Western societies which are rapidly losing social cohesion.

If you want talent, you usually have to pay for it. This is simply a type of talent which is overlooked in our current economic paradigm, and often deliberately so.