Six months before my 40 birthday I “retired” from engineering and became a full-time dad. Since then I occasionally ask my wife, “Do I need to get a job?” Her reply: “You can if you want.”

So, I keep all of my engineering books, just in case I want or need to get an engineering job again.

I decided to become an engineer when I was 17. My dad helped me with this decision when I applied for college. Deciding what to become — in my case — was partly a process of elimination and partly a process of answering questions similar to those shown in this Venn diagram.

I asked myself questions that centered on the following thoughts:

Choose something in high demand - so I won’t be without a job.

Choose something that pays well, so that I can work fewer hours.

Choose something that I’m good at, or at least not too bad at.

Choose something that I like, or at least can put up with.

The italicized portion in 2 was not part of my thinking at the time. Rather, my thinking was, “so that I can live a wealthy lifestyle.” Relative to most of the other 8 billion people in the world, I’m wealthy, but relative to my teenage expectations, I’m not as wealthy as I hoped I’d be. That’s okay; I think the more important outcome of having a job that pays well is that you’re able to get want you want in fewer hours of work.

So with these thoughts in mind I narrowed my career choices down to doctor, lawyer, and engineer. Clichéd yes. Eliminating lawyer from this list was easy. Compared to the best students in my high school English class, I wasn’t a very good reader or writer. So, this left me with doctor and engineer.

Here’s where my dad really helped out. He setup two days for me to shadow an orthopedic surgeon that lived in our town. My overall take-away from these two days was that I didn’t want to touch the patients in the clinic and I that I passed out when I got up close to the open incisions in the surgery room. So this eliminated doctor from the list.

Next up, was to decide what kind of engineer to become. This actually took years to figure out, but at 17 I started to collect information about the various branches of engineering. I spent a day with a civil engineer that worked for the City of South Lake Tahoe, and another day with a mechanical engineer that worked for the Omohundro Company in Minden, NV.

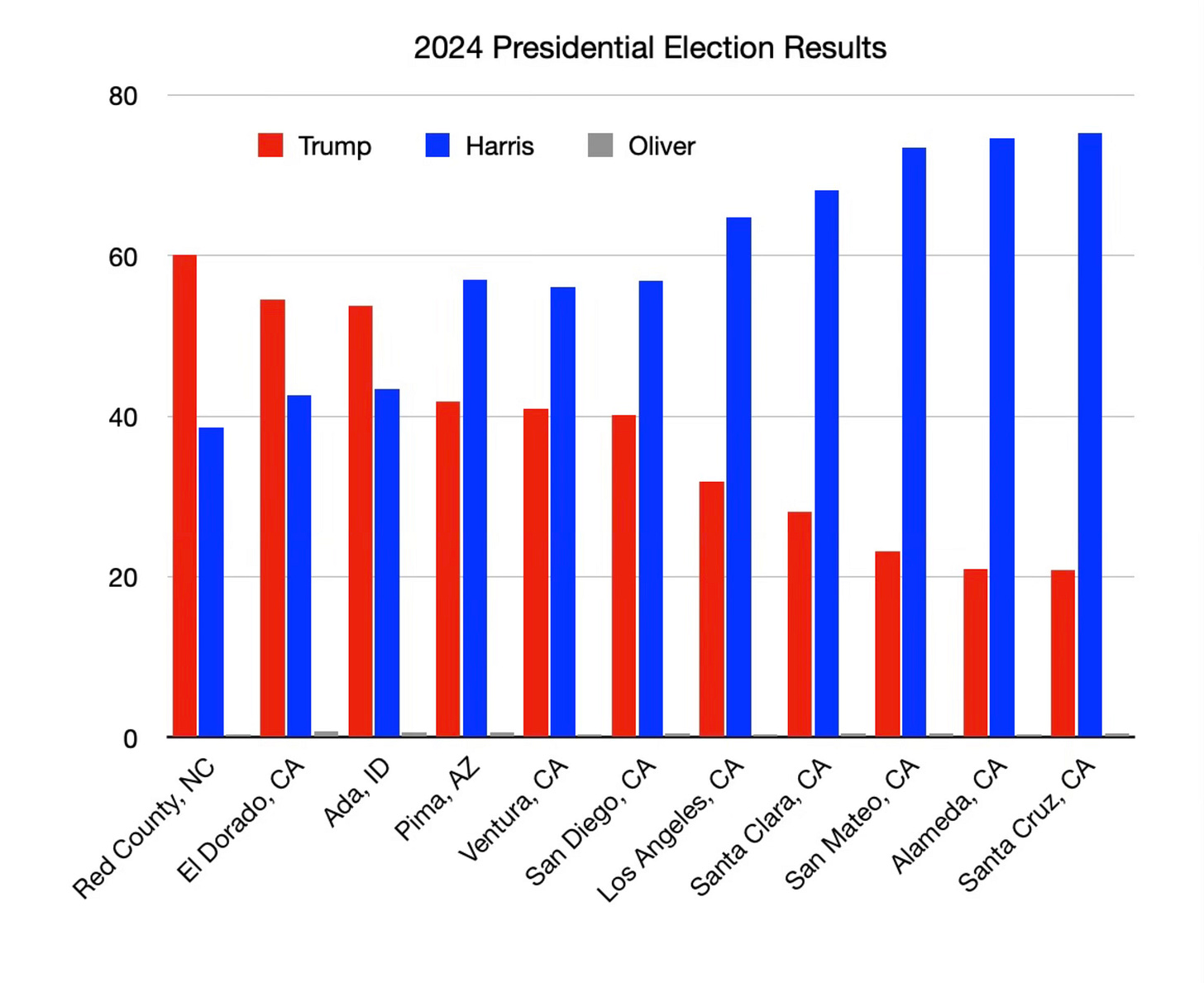

Seeing what the civil engineer did was crucial in my decision not to become a civil engineer. When he drove us around the city showing us the things that he had designed, I was not at all excited. “I designed this intersection,” he said. It was a beautiful intersection with great looking stop lights and sidewalks, but I was not interested in designing intersections or gutters. This didn’t fully eliminate civil engineer from my list, but it did put it at the bottom of my list. (One upside of being a civil engineer is that you can earn a decent living in a place like Lake Tahoe or a red county like I live in now).

On the other hand, the mechanical engineer that I visited showed me some cool stuff. He was using a CAD program called Pro/E to design high performance sailboat masts. In addition to this computer program I liked the feel of the factory floor where these carbon fiber parts were being made.

At the time, I didn’t know much about computer engineering, chemical engineering, electrical engineering, or material science, but I used a similar process of elimination here too. I wasn’t that good at, or that interested in high school chemistry, so that pretty much eliminated chemical engineering and material science.

In my case, I had a few more years to decide on what type of engineer I wanted to become because I majored in something called the 3/2 Dual Degree Engineering Program, which consisted of three years of study at U.C. Santa Cruz, obtaining a B.A. in humanities followed by two years of study at U.C. Berkeley obtaining a B.S. in engineering. (At Santa Cruz I majored in economics mainly because the investing game that we played in high school economics was fun).

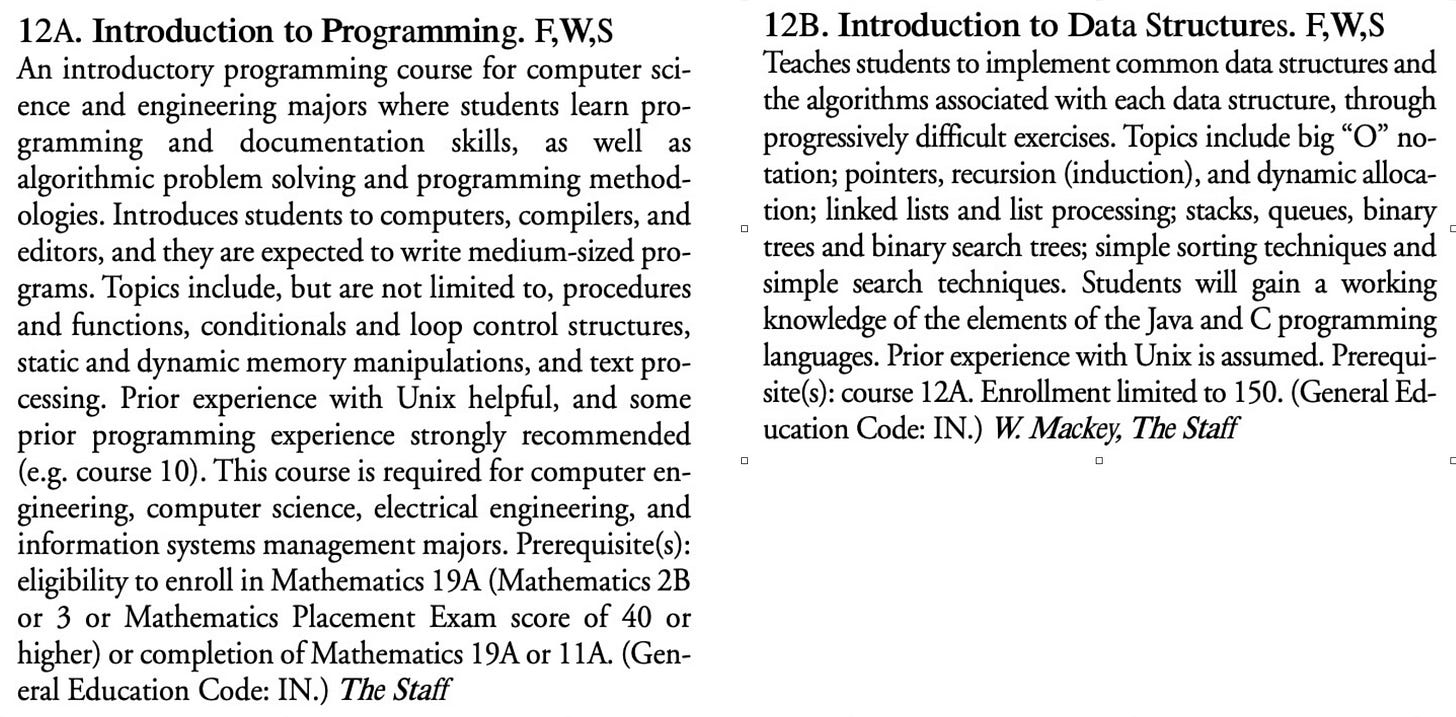

Throughout college I enjoyed looking through course catalogs, reading class descriptions, figuring out what classes I might take, and when I might take them. Rather than take the less-technical Pascal programming class for non-computer-science majors, I decided to take CS 12A Introduction to Computer Programming that used a simple version of C.

I loved this class. Programming was extremely satisfying, and even fun. So much fun that I took the next two courses in the series, CS 12B and 12C.

These three classes were some of the best classes that I took at UCSC. The professors were top-notch and the students were really bright. I aced each of these classes and took a summer job at an internet start-up called NetCarta in Scott’s Valley, CA. This was the summer of 1995, so the web was still pretty new, though certainly beyond primitive.

Cutting-edge interview questions in my case were: “Do you know how to download?” “Do you know how to upload?” Fortunately, I had good answers to these questions even though downloading and uploading were still pretty new concepts.

In this job, along with other “Cadets,” like myself, we edited web-maps. These were the days when search engines didn’t work very well. We had our favorite search engines. AltaVista was arguably the best, but you would often use a few different search engines in an attempt to find what you were looking for.

As an alternative to search-engines, NetCarta was making maps of the web. A concept that has since died. Cadets like me cleaned-up the raw maps produced by an automated map-making program, correcting their errors. Usually this consisted of checking each link in the map making sure it wasn’t broken (e.g. 404). If broken we would simply “trim it off” with one or two mouse clicks. It was a mindless job. Each day we cleaned-up scores of maps. Maybe 100 or 200 maps per day. Our boss would motivate us by creating competitions to see who could clean-up the most maps.

Midway through the summer we Cadets were burnt out. For most of the summer we shared one or two big rooms, with our desk around the perimeter with our backs to each other. As expected, like many office employees, we would take breaks from our work to surf the web. Sometimes this meant surfing porn. “Hey check out this one!” “That’s nasty!” There were few rules about surfing porn back then. We Cadets did it openly, only hiding it from our bosses.

Porn back then was much different than it is today. I won’t provide details, but there were no videos that I can remember. It was all stills, newsgroups, and prose. It didn’t take long for us to make ourselves sick from porn. There was only one female Cadet on the team - Sarah. She was tough to put up with a room full of guys looking at porn, sometimes for hours on end. One Cadet got addicted to porn. He went on a week-long binge — eight hours a day. Sarah was bummed. We were all like, “Stop dude. Stop.” But he continued. I doubt anyone told the boss. Instead we just avoided his monitor.

The most positive aspect of the job, was that one of the Cadets started programming little routines. He had taken an upper-division programming class and had enough skill and confidence to automate parts of his job. This was impressive, so naturally I wanted to take the same upper division course he did. I set out to take CS 101 the following year, but I never made it there.

That summer I became depressed, and especially depressed with computers. Largely, this was due to my first serous relationship not working out, but it was also due to the “PC culture” of Santa Cruz. PC culture being politically correct, not personal computer.

My mood continued into the fall quarter. Rather than take CS 101, I took CMPE 185 Technical Writing for Computer Engineers, which turned out to be my worst class at UCSC. The professor never wore shoes to class, nor seemed to shower. He was unable to excite me about writing a memo on “how to use email.” This lack of enthusiasm was more of a symptom of my mood however.

There was something even more troubling going on. During this time I came to hate computers in general. I even hated email. I suppose that I had been sucked into an anti-technology ideology. Certainly it wasn't just my reading of the Unabomber Manifesto while working at NetCarta, nor the hours of surfing porn with my co-workers at NetCarta, nor the frustration of looking for bugs in my computer programs, nor the occasional miscommunication disaster over email, nor the near constant refrain of “natural” this, “organic” that — “sustainable,” “renewable,” “diverse,” blah, blah, blah. I was drenched in PC culture.

This taps into a really big question about college versus the outside world. College, especially at UCSC, was overwhelmingly progressive. At 19 years old I was not equipped to deal with this ideology. I didn’t even know what progressive was unit years later. Progressivism simply overpowered me. I came to see my parents as “wrong.” They had raised me wrong. The world — in many ways — was wrong. Computer technology was evil because it wasn’t natural.

Then next quart at UCSC I did a field study in the Chilean Andes. This is what my ex-girlfriend recommended to help “cure” me of my depression. And so, for a few months I lived in the mountains in Chile with a group of Univ. of California undergraduates, mostly environmental studies students - lead by Dr. Tony Povilitis - a conservation biologist. Tony was actually a great guy even if I disagree with some of his environmentalist views. On that trip I decided that computer science was not for me. Civil engineering was more “balanced.” It was also better for the world. It was “sustainable.

After coming back from Chile, I was able to focus again. Being in nature and taking some time away from Santa Cruz worked. I enjoyed my Newtonian physics class and decided that I would major in mechanical engineering with my friends who were transferring to UC Berkeley with me.1

My classes at Berkeley were generally pretty good. I did fairly well there; worked really hard, probably too hard, and after graduation took my first salaried job working in motion control and robotics.

Compared to UC Santa Cruz, Berkeley engineering was straightforward. It was just hard work. Almost no political or ideological bullshit. As long as you showed up everyday, put in your quality work hours, it was doable. Somedays I would be laughing and crying at the same time, but I suppose I “enjoyed” the suffering and the challenge. The students were incredibly hardworking, and many super intelligent. It was a humbling experience. I was able to ace classes that I cared about, but found that it was hard to get As in all of my classes. The straight-A students in the Cal engineering program are special. I have a huge amount of respect for them. I do wonder if some of the top students are a bit unhealthy in their study habits though. It’s hard to say how hard they are working since things might just be easier for them.

Most importantly I enjoyed most of my classes in mechanical engineering. For the most part, each the core courses is fascinating: intro to material science, thermodynamics, fluid mechanics, heat transfer, and intro to electrical engineering.

Unfortunately when you’re done with mechanical engineering undergraduate you still “can’t do very much.” Unless, you’ve taken all of your electives in one area, you probably don’t have enough depth to solve “hard problems,” or design “the cool stuff.” The best work goes to those with graduate degrees or years of work experience.2 From there, you really have to work your way up to get better work.

I didn’t realize this while in undergrad and as a result didn’t pace myself properly. I put too much time into my studies at UC Berkeley and was burnt out when I was done.

Learning how to be an engineer at work is a huge undertaking. There's so much that college doesn’t teach you, so it’s important to pace yourself in college and save plenty of fuel for your first few years on the job.

Now let me mention some regrets about my undergraduate path.

Regret #1: For various reasons I wanted to major in electrical engineering and computer science (EECS) at UC Berkeley (see my excitement with respect to the computer science classes above), but being that it is a really difficult major, and being that my friends were majoring in mechanical engineering, I went with with mechE.

I’m not sure why certain majors are made more difficult than they need to be. The fact that EECS at Berkeley is difficult isn’t just because the math is difficult or because it’s more abstract.3 EECS is made more difficult because professors, students, and university incentives make it excessively difficult and become the system has grown that way. It’s a super competitive major. The same major at UC Davis or UC San Diego is probably easier because the students are of a slightly lower caliber and probably less competitive. Going to UC Berkeley helps open doors for you, but in my case, it closed the EECS door on me. I was just too wimpy to take on that major without my friends. Had I gone to a less prestigious college there’s a greater chance that I would have studied electrical engineering and computer science. This might have helped hold my interest in the working world because as you’ll see in Part 2 of this series, mechanical engineering at work can be pretty boring.

Regret #2: UC Santa Cruz was a very political experience. It was very progressive, which made me stronger in some ways, but I do not recommend attending a university with a strong political bias like UCSC. UC Davis or UC San Diego would have been much less political. And I’m not just talking about the professors. I’m talking about the students, the administrators, the city, and the county.

Regret #3: Though I didn’t discuss it much here, economics at UCSC was not that good. Econ 1 was a great class, but after that, I don’t have many positive things to say about my econ degree. Econ is probably great at certain colleges, like George Mason University, but in my case it was not that helpful. Okay, so it introduced me to many flawed economic ideas. That can be seen as “good” in a way, but overall it seems wasteful. There are better ways to spend your early twenties.

Regret #4: There are few women in engineering. The engineering fields are made up of engineers. If you don’t like to be around engineers, you may not want to major in engineering. Engineers tend to be more arrogant, less socially adept, and more competitive than other people. Fortunately, dating apps showed right after I graduated from college. Without Match.com and Eharmony, my dating life would have sucked.

Regret #5: Most engineering classes are taught be people who have never worked as engineers. The typical engineering professor has been in school his entire life, so he’s not going to fill you with wisdom about corporate life or how to solve problems in the real-world. Learning how to solve problems at work is greatly aided by having a mentor at work. Applying what you’ve learned in school to work takes more time than you expect. In some ways, learning on the job, working long hours, and teaching yourself with the help of mentors might be better than engineering school. Occasionally I’ve run into engineers at work that didn’t have engineering degrees. These engineers are sometimes some of the best engineers in the org.

Regret #6: An important part of engineering is being a skilled technician. There can be stresses between technicians and engineers. Some technicians (and even some technologists) look-down upon engineers because engineers lack certain basic technical skills that technicians sometimes have in abundance. There is a type of technician called a super-technician. These are people that have extraordinary abilities to build things in the shop. They often possess certain techniques and have exceptional hand-eye coordination. They can do things that are considered “black arts” that are not taught in engineering school, and can only be learned on-the-job.

Similarly there can be stresses and strains between fabricators and engineers. The most common type of fabricators are machinists, but they can also be opticians, plastic-injection molders, 3D-printing specialists, and other specialists that cut, grind, polish, bend, and shape materials to engineering specifications. Most engineers come to engineering through college. Fabricators are typically not degreed engineers. Their wisdom comes mostly through on-the-job experience. Engineers need to know what the fabricators are capable of. Without this, engineers can do the job. Fabricators know this and they use this knowledge as leverage against engineers. Sometimes the fabricators will “steal” work from engineers, bringing it into their house, giving it to their in-house engineers. This then makes you a project manager.

In summary, technician-experience and fabrication-experience is really important —it’s foundational to becoming a confident, skilled, and satisfied engineer. Prior to going to college, working as a technician or as a fabricator might be a good idea. A great deal of engineering knowledge depends on knowing what technicians and fabricators know.

If I had it to do over again I would put off my four-year college degree until I had about five years of experience working as a fabricator. In this five years I would get as much hands-on experience as possible and I would earn a two-year degree at a technical college or take enough classes at technical colleges to get me into some interesting high-technology fabrications houses.

Once I had this work experience under my belt I would then consider getting a four year engineering degree. If that went well, and I was still engineering my engineering career I would get a masters degree.

Benefits of the Engineering Major

Of the choices available to the college-bound, engineering is a really good major. It will teach you the fundamentals of science. Compared to other majors, engineering prepares you better to solve real-world problems. You will learn physics and math. You will learn how to read technical prose. Majoring in engineering will allow you to earn a decent living even if you don’t work as an engineer. As a major, engineering is relatively free of political ideology. If you major in engineering, it will be less wasteful of your time than many other college majors.

Notice that this is not a glowing review of the engineering major.

Okay, next up in this series will be a description of some of my engineering work experiences. As stated in the beginning of this piece, I “retired” from engineering at age 39. Some guys sit in the cube for 40 years before retiring. Is that something you can handle? Not sure I could handle it.

With that said, I had some great experiences as an engineer. “It worked out for me. Sort of. Then again maybe not.”

Should you become an engineer? I think it really depends on how you go about becoming an engineer. If you start out in a place where you’re learning hands-on and practical skills, the journey will likely be a better one than if you start out at an elite school where your teachers have little real-world experience. Without truly starting at the bottom of the technical ladder — as a technician or fabricator — your lack of practical skills can be a real handicap and source of stress.

Beware and consider alternative paths that make sense to you and fit in with the four questions in the Venn diagram above. Higher education is in many ways a mess, even the engineering fields.

By the way, this post isn’t just for you. It’s for me. I’m still trying to figure out what to do next. Should I get back into engineering? I don’t need to, but it might be a good thing for me. Maybe I should start my own business using my engineering skills?

This post also helps me clarify my thinking as a mentor for my kids. My kids need help deciding what classes to take and career paths are good ones. Without understanding my own career path, I’ll likely bumble around in my advice to them. The less bumbling the better.

This entire time at UCSC I was majoring in economics as part of my 3/2 Dual Degree Program, but econ was just for fun. I was never going to make it my career. I was always going to be an engineer.

Don’t expect to walk out of undergraduate engineering and get the choicest of work even if you graduate from the best university. The degree mostly just gets you in the door at work.

The math might even be easier in electrical engineering than in mechanical engineering. Conceptually EECS is more abstract and thus probably more difficult conceptually.