Did ChapGPT Blow Smoke Up My Ass?

Free speech, the First Amendment, and the myth of the Fourth Estate.

Paul Krugman recently wrote a piece titled, “Departing the New York Times.” I don’t have much to say about it, but that piece was brought to my attention by someone I follow here on Substack named Amanda Claypool.

I know very little about Mrs. Claypool. I probably started following her a few months ago and have since forgotten exactly what triggered my following her — but I find her posts insightful, and after reading her About page I can see why I decided to subscribe to her newsletter. Concerning AI, she says, “'We’re living in the midst of a Gutenberg Press moment.”1

In the middle of the 15th century, a German goldsmith invented a device that changed the world.

It wasn’t so much about what the printing press could do — reproduce the written word in the form of books, pamphlets, and newspapers — it’s how that device was used to gradually change society over time.

At the time of its invention, The Bible was what Google is today. It was the source of all information that guided life.

Because peasants weren’t educated and illiterate people didn’t demand books, there wasn’t a need to make knowledge accessible, much less transfer it between classes.

That changed with the printing press.

Anyone with a thought could publish it and share it with the world.

So they did.

The church was no longer the sole distributor of information. And as medieval feudalism gave rise to a new economic system — capitalism — the church’s power waned.

New ways of governance emerged. Ideas around freedom and liberty took shape. Over centuries the proliferation of new ideas has culminated in the world we live in today.

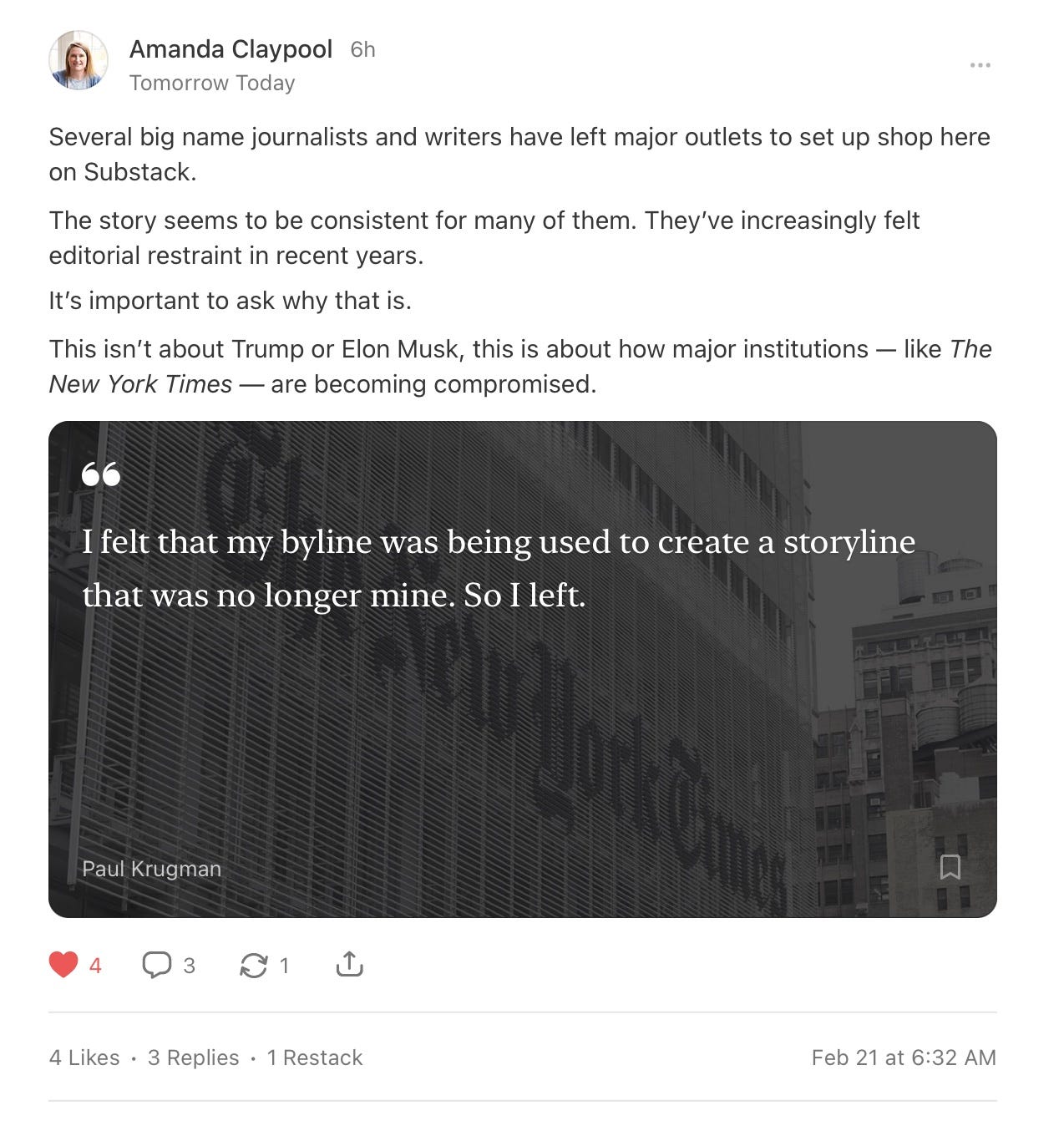

Yep, that sounds like a newsletter I would follow. Anyway, after reading Krugman’s piece explaining why he left The New York Times, I started chatting publicly with Amanda on Substack. You can read the thread here, but I’ve also cut and pasted it below in full. Here’s how it begins:

I found it interesting that she sees Krugman’s departure as being related to a reduction in free speech. Sure, it’s related to free speech, but free speech has a specific meaning to me. What is this?

It begins like this: The purpose of government is to protect your natural rights. In giving this protection duty to the government we risk having the government violate our rights. Hence the Bill of Rights (and other parts of the Constitution) serve to protect us from arbitrary power of the government. In particular the First Amendment protects our freedom of speech and freedom of conscience. And the Declaration, which gave rise to the Constitution, states that, “All Men are created equal, and thus deserve equal treatment before the law (i.e. by government).”

Next we might ask whether, “free speech” concerns the freedom to say “anything you want” within private organizations? I say, “It depends.”

What do we mean when we say “free speech?” And what is the scope of “free speech?”

This can get confusing. Let’s think carefully here. And I admit, I’m still learning about this topic, so bear with me as I think it through. Indeed, I might be confused and ignorant on this topic. But I’m learning.

The purpose of government is to protect our natural rights, hence our government should protect our natural speech rights from domestic and foreign threats.

We empower the Constitution, and the Constitution empowers the government to protect us from violations of our rights, including — but not limited to — natural rights of speech, religion, freedom of the press, dissent, complaint about one’s government, freedom of assembly and association, to hire and fire as we need to, freedom of expression, and freedom of conscience.

But the devil is in the detail. Much depends on our property rights and on the context of our particular situation.

For example, does the First Amendment apply to private, voluntary agreements like Paul Krugman’s employment contract with The New York Times?

I’m not sure. Perhaps, only if our property rights are violated by The New York Times.

For example, The New York Times cannot force Paul Krugman to bake a cake. He is not their slave. Krugman is free to opt out of his employment contract. Likewise, Paul Krugman cannot force The New York Times to bake a cake. Nor can he necessarily bake cakes of his choosing on their dime. The New York Times has rights also. They get to choose how to spend their resources. Krugman cannot just take their property and use it as he wishes. Krugman and the Times have to respect each other’s rights — particularly their property rights.

If The New York Times violates Krugman’s property rights, the government should bring justice to his situation. So, what are his property rights? It takes a while to explain, but to save space and time, I would say that he cannot be made a slave, nor can someone take his stuff. Nor can he make The New York Times his slave, or take their stuff. The Golden Rule applies, as it almost always does. Perhaps we should call this rule, the rule of mutual respect for property rights.

The First Amendment is a special agreement that guides our treatment of each other. Milton Friedman taught me this. It is a form of the Golden Rule.

In its elementary school form the First Amendment says:

I’m here to learn. I respect myself and my rights. I respect others and their rights.

In a classroom setting students must follow the rules of the classroom. Doing otherwise prevents learners from learning and the teacher from teaching. We can take this simple form of the First Amendment and apply it to our lives in general. I will leave that as an exercise for you.

So let’s summarize carefully. The First Amendment is a rule of mutual respect for property rights that allows us to learn, grow, discover and be. This is not limited to religion in the narrow supernatural sense, but rather applies to all learning. The First Amendment protects all learning and all education, including education by educators of all types and learners of all types. It is a universal statement about learning and respect, applied to all people.

In fact, this is the most important message of Christianity. God tells us to love one another and to love him. But we needn’t make our lives difficult. This is simply a statement of mutual respect and learning.

It applies to government as well. And our relationship to each other through government.

Government is a dangerous vehicle for maintaining order. It concentrates power in the hands of the few in order to protect the many.

So I’m ready to write down a rule explaining the scope of the First Amendment. The First Amendment is a rule of mutual respect that applies

Between each of us

And between each of us through actions of government.

The Declaration of Independence affirms this: “All Men are created equal.” And then goes on to say, “We colonists deserve equal treatment. King, you have not respected us. Hence we are freeing ourselves from your government and creating a new government based on mutual respect of property rights and learning. In doing so we are making a promise to each other to follow the Golden Rule, hence the First Amendment.”

Okay, done with that (for now). Let’s get back to Krugman.

Krugman must follow the rules of his employment contract with The NY Times. As an employee, they can censor his work-related speech, even his op-eds. His work-related speech is smaller in scope than his public speech. Per ChatGPT:

Op-eds are often found in a section opposite the editorial page, hence the name.

Editorial: Reflects the official opinion of the publication.

Op-ed: Presents the personal opinion of an external writer or contributor.

Op-eds are still the private property of the newspaper. If Krugman wants to speak freely he should move to Substack (which he has done).

So what exactly is Amanda Claypool concerned about? Is she concerned about the First Amendment? Well…I’ll let you read her statements for yourself and decide.

My conversation with Claypool lead to an interesting place concerning the First Amendment - in particular with regard to the meaning of “trusted” news organizations and “public goods.”

If you’ve been reading this newsletter for a while this shouldn’t surprise you: I write about the First Amendment regularly and my views on it are not widely shared. I hold a rather unorthodox view regarding the First Amendment. I believe it should be expanded to include education — and all forms of learning — in addition to religion.

And in the same vein, perhaps I’m trying to nudge the definition of religion toward a more expansive definition that includes education and its subsets such as philosophy, science, biology, archeology, AI, the internet, journalism, libraries, and probably much more.2 In other words, keep the government out of the learning process as much as possible. DEI, “Covid science,” and progressivism in general instigated my interest in understanding and expanding the scope of the First Amendment.

Aside: It seems I’m not completely alone on expanding the scope of the First Amendment. Recently I discovered that one of my favorite thinkers and authors, James Otteson wrote a book chapter titled “Freedom of Religion and Public Schooling” that pushes a viewpoint very similar to mine. The First Amendment should include both religion and education under the rubric of freedom of conscience. And in my notes on that chapter I ask, “Who is the press?” That note pertains to this post.

Maybe that’s the question I need to pose to Amanda Claypool and others, “Who is the press?” The press is an educational institution. Might they also be considered a religious institution? Yes, in the ideological sense they are. Each of us has an ideology. We each have our biasses and our viewpoints. Each of us has unique “op-eds.”

Likewise, universities are ideological — full of biased professors. We don’t like to admit this, but it’s true. Journalists are biased and self-interested, just like the rest of us. They can’t help it — they’re human too.

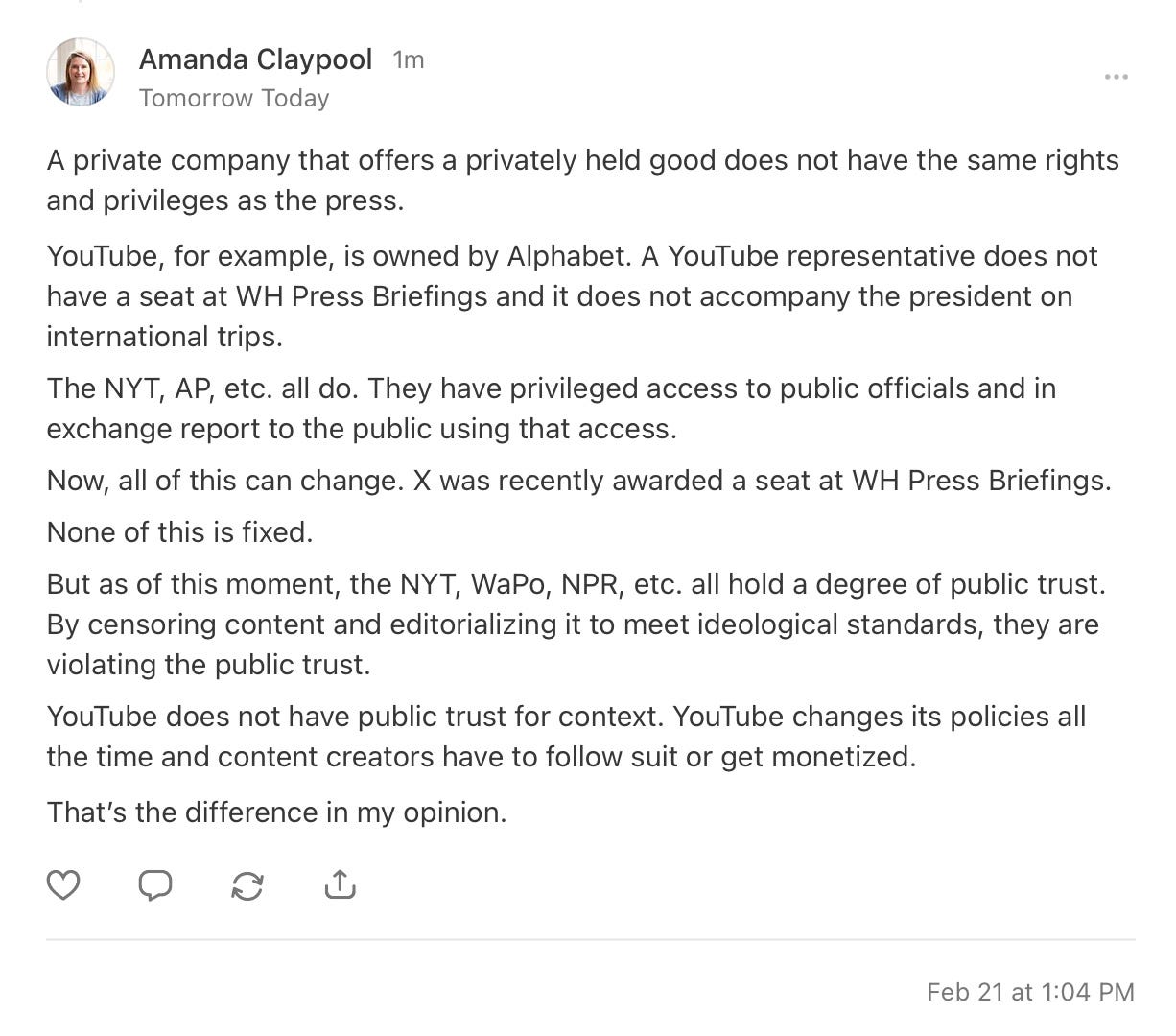

As you’ll see in my conversation with Mrs. Claypool, she presents a commonly-held view regarding the press. In her view the press has different rights and privileges than regular private companies. The press it seems has more rights, and more privileges in accessing public officials. She writes:

A private company that offers a privately held good does not have the same rights and privileges as the press.

YouTube, for example, is owned by Alphabet. A YouTube representative does not have a seat at WH Press Briefings and it does not accompany the president on international trips.

The NYT, AP, etc. all do. They have privileged access to public officials and in exchange report to the public using that access.

Why should some private entities get more rights and privileges than others? One response is that public officials have the freedom to choose which journalists they invite to their press meetings. Fair enough.

But doesn’t this give certain people an advantage to push their ideology. It gives the press more power. It “respects” the establishment of the press, giving subsidies, favors, and aid to the press. Is this okay? What are the alternatives?

Let’s investigate this further. Public officials may invite their preferred journalists to their “private/public” events, just as Donald Trump invited certain religious establishments to his inauguration; just as the Executive Branch may purchase expensive subscriptions from certain news outlets such as Politico; and just as the federal government may fund certain ideologies (such as DEI) through USAID or the Department of Education.

Is there a common theme between these examples? Is there consistency in this theme? Or have I gone wrong in my extrapolation?

Let’s be methodical here. Claypool might be concerned with something different than me, so let’s set her viewpoint aside (for a moment), but let’s not forget about it entirely because it might be important.

In my view the First Amendment prohibits Congress from making “law respecting an establishment of religion,” but it doesn’t confer special rights and privileges on one private entity over another. All private entities are treated equally.

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

It say Congress shall make no law respecting or prohibiting or abridging. Yet it seems that Mrs. Claypool and others see the First Amendment as respecting the press over and above the rest of us.

Is this just due to limited space in the briefing room? We can’t all fit into Air Force One, nor into the White House. So what should we do? How do we treat each other equally when there’s only so much room in the government meeting room?

Let’s follow Claypool’s thinking (not to pick on Claypool, but because I believe it represent a commonly held view) that we should try to understand. Notice that she introduces something called the “Fourth Estate.”

What is the Fourth Estate and what is its role? “The press makes sure you get to [say what you want].” In her view the role of the press is to “hold truth to power.” Reasonably people will disagree with that view, perhaps seeing the press as spreading propaganda.

She doesn’t see the press as “private entities like I do.” In her view the press plays a public role and can be considered a “public good.” Hence, editorials cannot and should not be whitewashed “to comply with an ideology” — even by the editors of that newspaper. Doing so is “propaganda.”

In my view and perhaps yours, NPR, WaPo, and NYT can reasonably be viewed as “propaganda companies.” They present a view that some consider propaganda-like. But Amanda says,

Maybe the solution then, is to reclassify NPR, WaPo, NYT, etc. as private propaganda companies?

Yes, please classify them as “private propaganda companies” if that helps us see them as private companies pursuing profit and behaving just like any other private companies pursuing profit. Of course propaganda might be too strong a word. What word would you use to describe these companies?

Why would we expect the press to act any differently than other private companies? Press companies are run by humans. We should expect the exact same behavior from journalists — on average — that we expect from other humans.

Sure journalists say they are pursuing truth, but so are the rest of us. And we won’t all agree on the truth. Hence our religious differences, and hence the purpose of the First Amendment.

I home in on her view of op-ed columns. Let’s see how she responds.

Okay, so she backed off the op-ed column topic, which in my view was what started this conversation. We were talking about an op-ed columnist named Paul Krugman. He left The New York Times because he didn’t have sufficient editorial freedom over his work. Claypool’s perspective is that “major institutions - like The New York Times - are becoming compromised” and that:

Several big name journalists and writers have left major outlets to set up shop here on Substack.

The story seems to be consistent for many of them. They've increasingly felt editorial restraint in recent years.

I then ask, “Comprised in what ways? Is there a pattern?”

She responds with:

Reduction of free speech.

When you have journalists from NYT, WaPo, CNN, and NPR all leaving and saying the same things about ideological homogeneity and increased editorial control over what's being published, that suggests there's a fundamental issue here.

Most conversations about the media are focusing on individual outlets. But if you look at them collectively, it seems like ideological capture is much more pervasive than most people realize.

That's a problem because a lot of folks are still consuming "news" from these publications. If it's being heavily editorialized, it's no longer news. And if you have teams of people at these organizations dedicated to routing out "misinformation" you no longer have free speech.

Interesting. She sees this being about free speech. I don’t. Here’s my view:

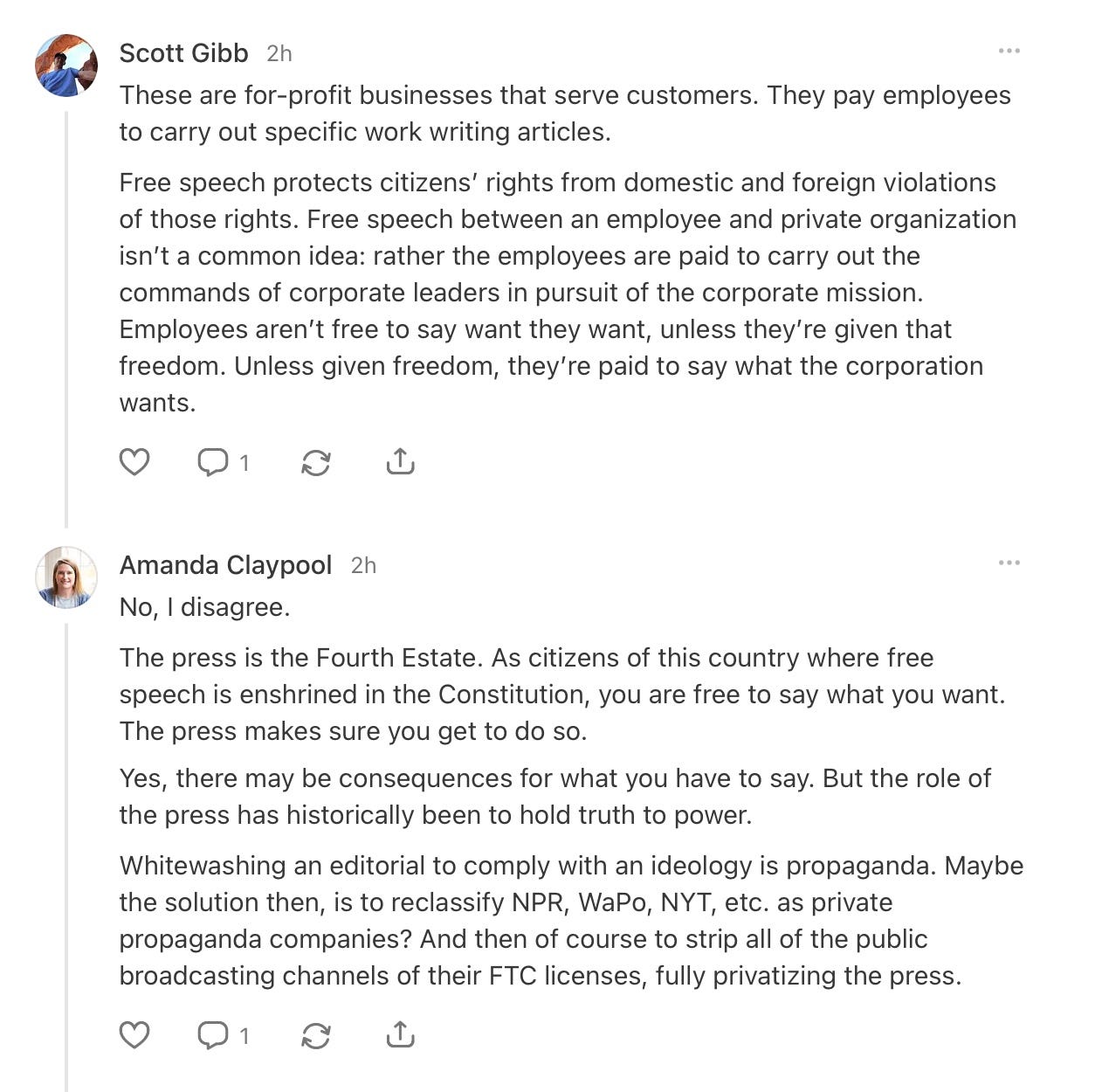

These are for-profit businesses that serve customers. They pay employees to carry out specific work writing articles.

Free speech protects citizens' rights from domestic and foreign violations of those rights. Free speech between an employee and private organization isn't a common idea: rather the employees are paid to carry out the commands of corporate leaders in pursuit of the corporate mission.

Employees aren't free to say want they want, unless they're given that freedom. Unless given freedom, they're paid to say what the corporation wants.

She responds with:

No, I disagree.

The press is the Fourth Estate. As citizens of this country where free speech is enshrined in the Constitution, you are free to say what you want.

The press makes sure you get to do so.

But when I focus in on the private property rights of journalists concerning their op-eds, she backs away.

No. My comment is about the media writ large, not op-ed columns specifically.

The media is a privately held public good just as airlines are. Airlines interface with public institutions just as the media does.

She now introduces a new concept (to me): a privately-held public good. The media, like airlines are in a special category.

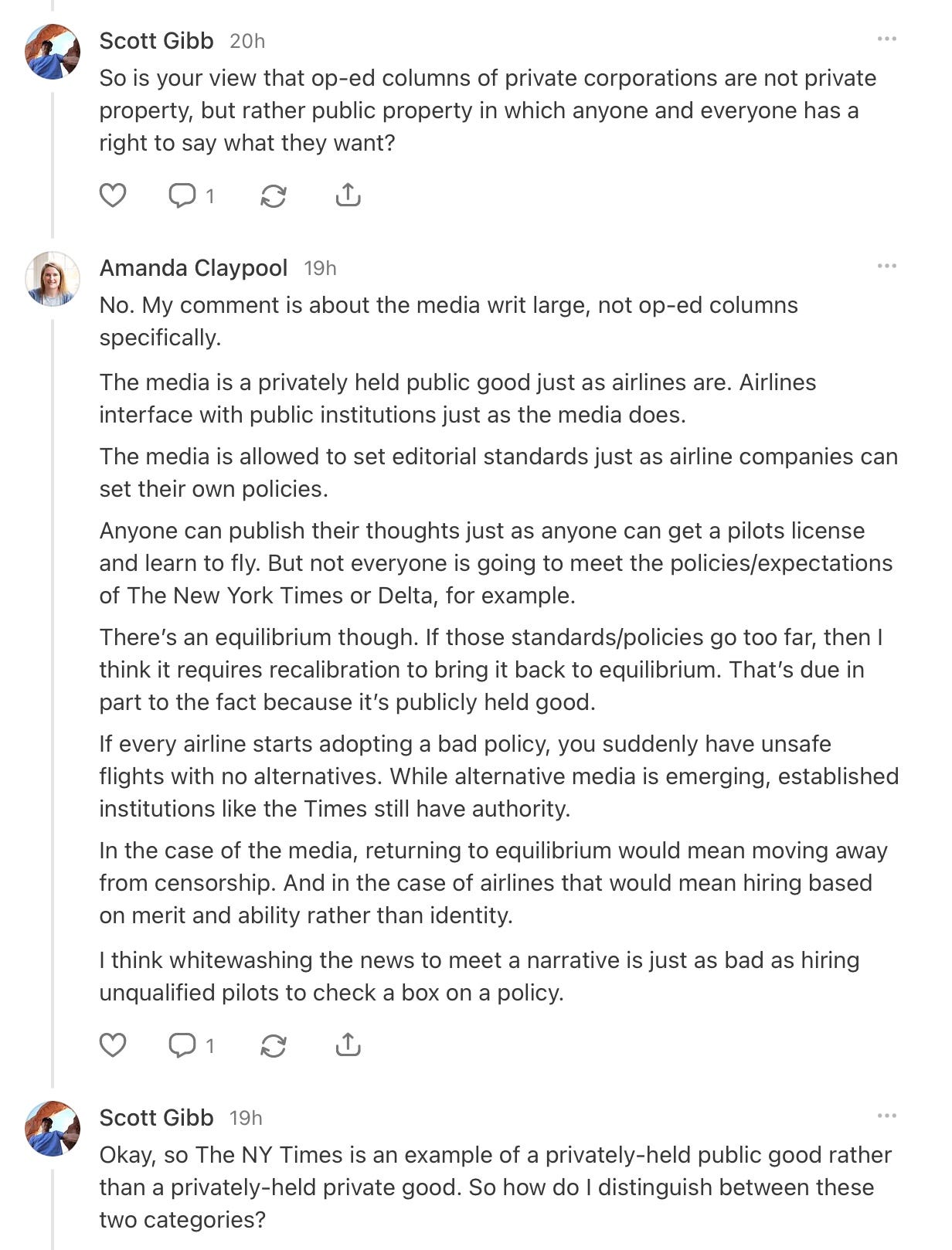

I ask her how to distinguish between these categories:

Okay, so The NY Times is an example of a privately-held public good rather than a privately-held private good. So how do I distinguish between these two categories?

Notice that she says,

“A private company that offers a privately held good does not have the same rights and privileges as the press…[Unlike Youtube] The NYT, AP, etc. all do. They have privileged access to public officials and in exchange report to the public using that access.”

So certain press outlets are awarded with more privileges. Which ones? She says, “X was recently awarded a seat at WH Press Briefings.”

Okay. Makes sense. In my view Elon Musk is now part of the Trump propaganda wing. In her view X has more rights and privileges than YouTube.

Why doesn’t YouTube have a seat at WH Press Briefings? She says:

YouTube does not have public trust for context. YouTube changes its policies all the time and content creators have to follow suit or get monetized.

So X has public trust but YouTube doesn’t?

This seems very subjective. Who is deciding which companies get access to WH Press Briefings? The Trump Administration! And the Trump Administration is not the public. The Trump Administration is made up of humans acting in their self-interests.

So perhaps this is just a semantics issue. Maybe if we dig down we’ll agree on things. Maybe we just need to define terms better.

But notice that she says

Now, all of this can change. X was recently awarded a seat at WH Press Briefings.

None of this is fixed.

Let’s be clear on what she just said. I specifically asked her to help me understand how to distinguish between a “privately-held public good” and a “privately-held private good.”

She gives the example of YouTube and says, “That’s the difference in my opinion.” “YouTube does not have public trust for context.”

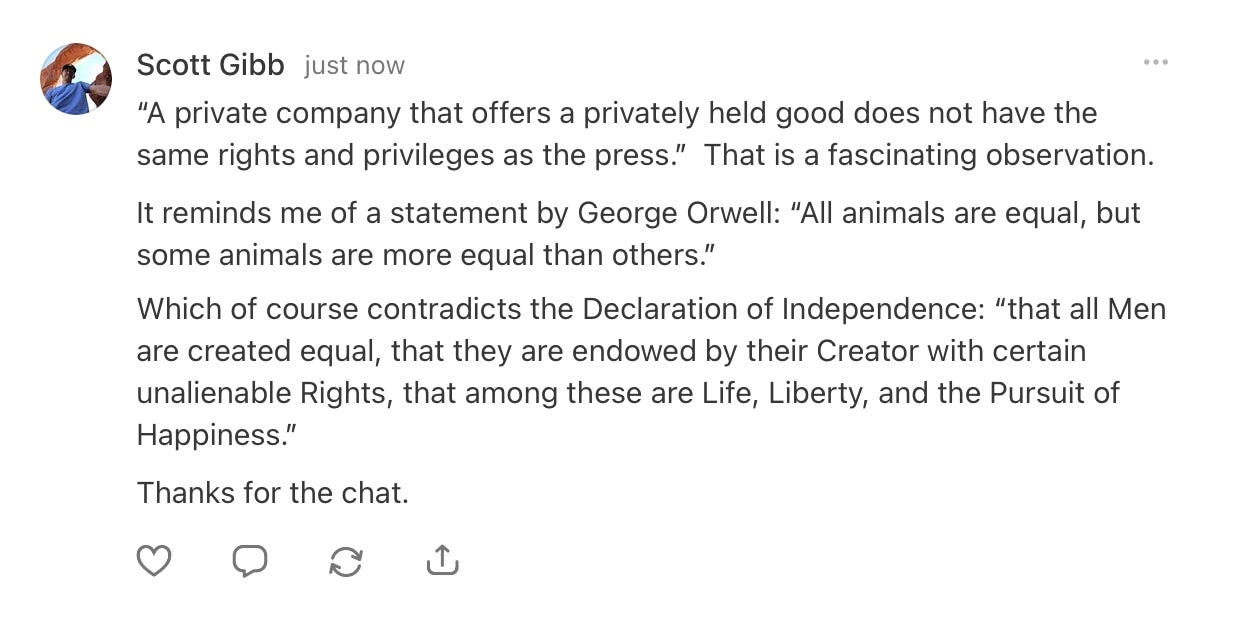

This all seems very arbitrary to me, subject to the whims of “Dear Leader.” What’s my response to her? I say:

In other words, X is more equal than YouTube because the Trump says so, which of course reminds me of the Declaration of Independence, which I actually read and commented on recently.

Perhaps I’m a bit out of line to invoke the Declaration, but is she defining a public good poorly? I need your help her. She is saying a privately-held public good is a public good because it has the public’s trust.

No, I see this differently. Certain media organizations are favored by certain politicians and because of this favoritism they receive special privileges.

Accepting this perspective might cause her to see these media organizations as private propaganda companies. But perhaps she’s reluctant to do that because…I’m not sure why….it’s not very romantic perhaps? It’s disappointing to realize that humans run the Fourth Estate. It’s not run by angels either.

If Men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and the next place, oblige it to control itself. — James Madison

For her the Fourth Estate is special — perhaps honorable and free of the conflicts of other, lesser forms of human potential. No, after reading this I can’t see her holding that view.

The Fourth Estate is not more equal than others. “All Men are created equal.”

In her most recent response to me she writes:

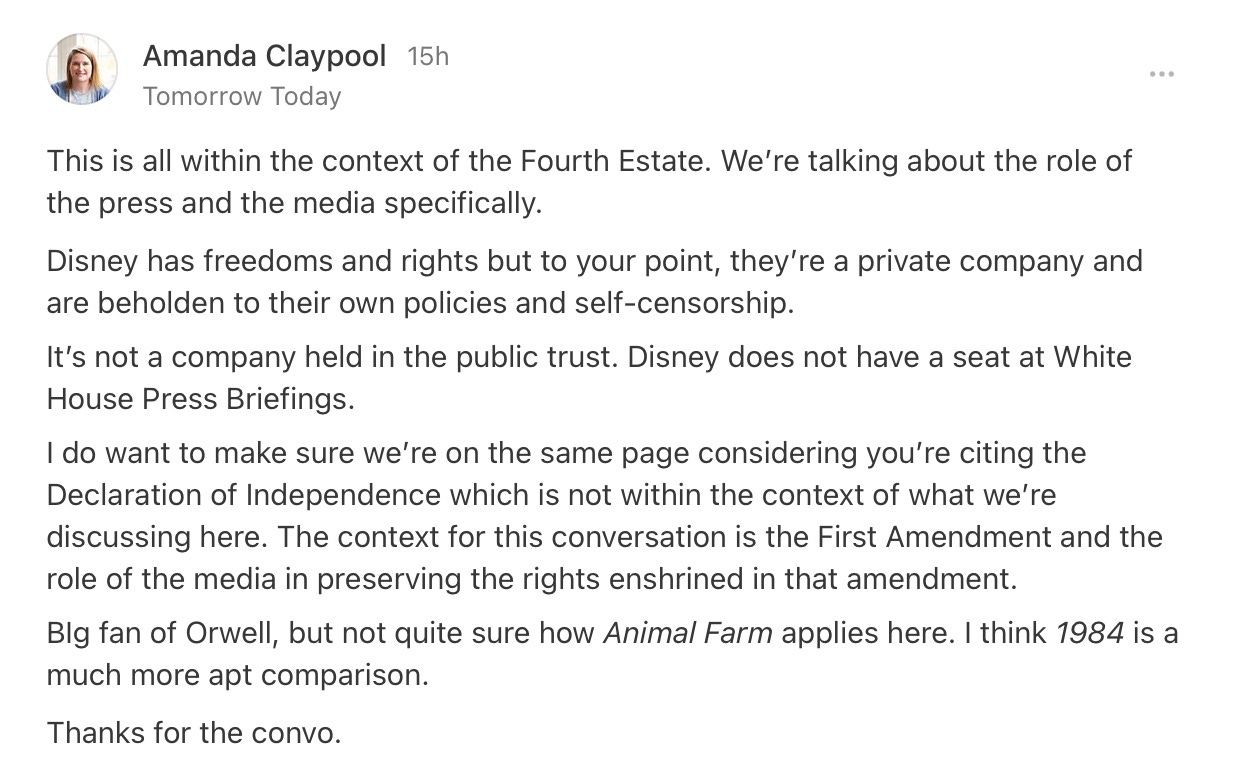

She doesn’t see how my reference to Animal Farm applies here. “1984 is a much more apt comparison,” she says.

The Declaration of Independence is, according to her “not within the context of what we’re discussing here.” Why not? Because “This is all within the context of the Fourth Estate. We're talking about the role of the press and the media specifically.”

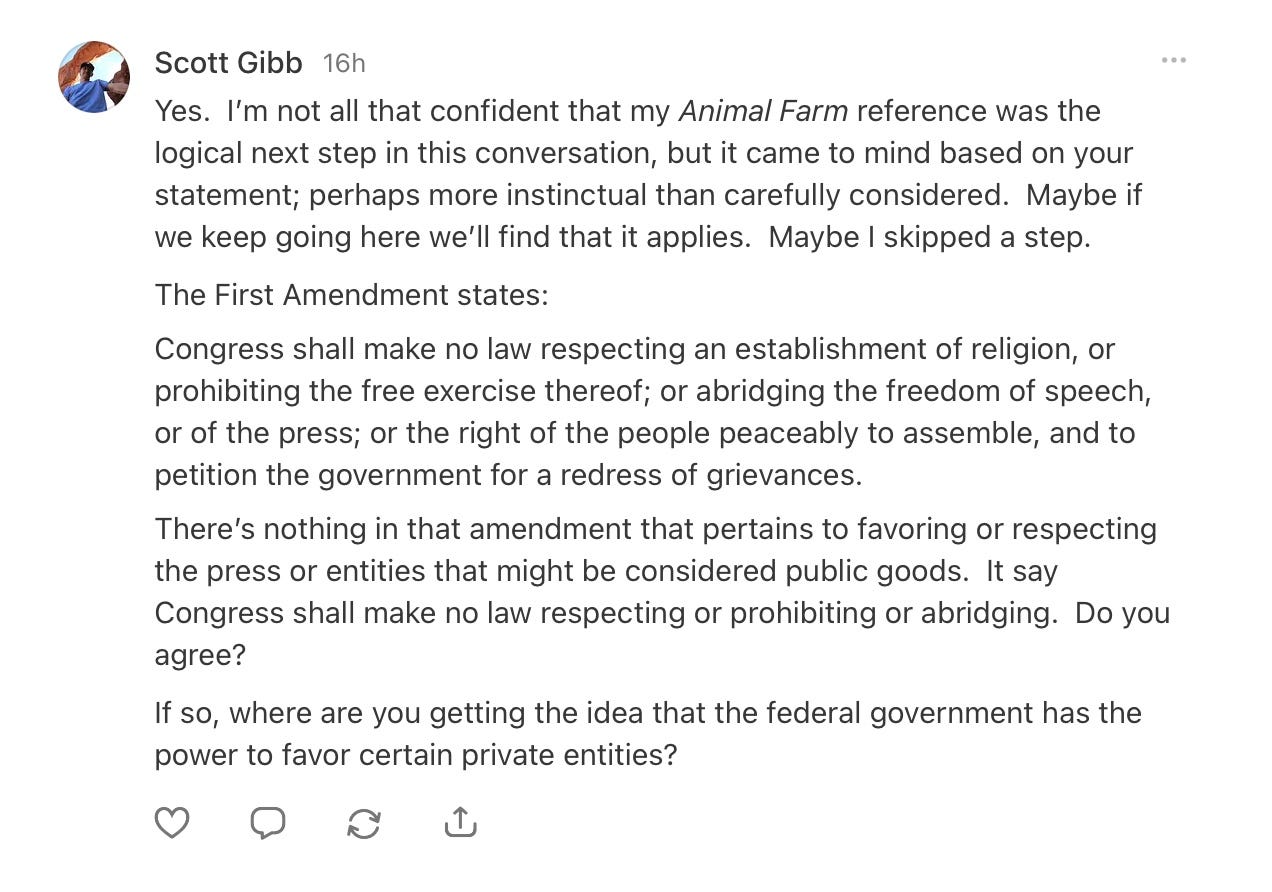

Maybe she’s right. I’m open to being wrong. Here’s my most recent response.

I read the First Amendment with her:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

And then I ask:

There's nothing in that amendment that pertains to favoring or respecting the press or entities that might be considered public goods. It say Congress shall make no law respecting or prohibiting or abridging. Do you agree?

What is my goal here? I would like her to stop seeing the press as a special entity that deserves to be called a “public good.” Instead I would like her to see the press as she sees other private entities. Just regular private entities.

I would like her to see that Donald Trump gives privileges to certain news outlets, based on his preferences, and his self-interests. All politicians do this to some extent.

So this is more than just a semantics issue. This is a difference of opinions in the nature of the press. I don’t believe the First Amendment gives the press any special rights or privileges. Read it for yourself and show me where is says that.

I believe Amanda Claypool believes in a myth about the Fourth Estate. What is this myth? In the style of Michael Huemer let’s state this myth.

Myth

The Fourth Estate is similar to a fourth branch of the U.S. Government. It is comprised of trusted press, news, media, and journalistic outlets, which serve to monitor and influence the other three branches of government. The Constitution delegates special rights and privileges to the Fourth Estate through the First Amendment granting its member organizations the status of “privately-held public good” and hence access to public officials. This status can change however. None of it is fixed. Violating the public trust causes a press organization to lose such status and hence their access privileges. Members of the Fourth Estate are not privately-held propaganda companies, but rather trusted companies that have special rights and privileges above and beyond less trustworthy companies, (like Youtube, which change their policies all the time).

Is that fair to Amanda Claypool? I don’t mean to pick on her. I’m trying my best to represent her view objectively. If her view is a widely-held one then this is an important topic to discuss, otherwise this post may not be pertinent to you.

In order to figure out how other people think about this issue, let’s ask ChatGPt.

Thank you ChatGPT. I love that she said the term “privately-held public good” is a bit of a paradox. I agree, it’s “a bit of a stretch.”

ChatGPT says:

It might be more accurate to describe The New York Times as a privately-held company that provides public service through journalism-important for societal information, but not technically a public good in the economic sense.

Okay. I like her honesty. Let’s remind ChatGPT that some people despise The New York Times and Paul Krugman.

Okay, good. I like ChatGPT, but is she just blowing smoke up my ass? Perhaps ChatGPT is an ass-kisser?

Yes. I like ChatGPT. The NY Times is not a “public good,” rather

it has the power to influence the public in ways that are not serving society's best interests. So, "privately-held public harm" would capture their critique of the NY Times' influence in a way that critiques its harmful role rather than its constructive one.

Wonderful! See I was right!

I admit, I’m sympathetic to anarcho-capitalism, so it’s not surprising to me that I would push an idea that seeks to expand the First Amendment, or the meaning of religion within the First Amendment to include education and perhaps all learning.