Let’s read some excerpts from Richard Vedder’s book, Restoring the Promise: Higher Education in America. All of these excerpts utilize ideas from Adam Smith.1 In fact, after reading Vedder’s book, I simply went to the index and looked up all the instances in which Smith is referenced. I’ve arranged these excerpts in a way to tell a narrative of sorts. For each one I include the page number so you can more conveniently research further if you choose.2

On page 50 Vedder writes:

…Adam Smith made a valid point some 240 years ago in the Wealth of Nations when he said that university endowments reduced incentives for faculty to be good in the classroom (since teachers were no longer reliant on their students directly for their income), to the point where "in the university of Oxford, the greater part of the publick professors have...given up altogether the pretense of teaching." Government subsidies, being similar to third-party payments, very likely have the same impact that endowments do.

In other words, government subsidies to higher education have the same impact as university endowments: both reduce incentives for faculty to be good in the classroom.3

This is a common theme in Restoring the Promise: getting the incentives right. For example:

The ultimate use of incentives was suggested by Adam Smith in his magisterial Wealth of Nations over 240 years ago: have students directly pay professors for their services. Extending Smith's analysis, the professors, in turn, could contract with packagers of courses to create degrees, either through traditional universities or other providers. These packagers of degrees can provide administrative and other services (e.g, classroom rental) necessary to ultimately providing a diploma certifying the student has attained a reasonably high level of competence. Professors who are popular can charge higher fees to more students, obtaining higher revenues. To be sure, popularity and true learning are not perfectly correlated with one another, but incentivizing professors to be interesting and relevant is in itself not an altogether bad thing.

That was from pages 313-314.

Does this sounds like a good idea? To have students directly pay professors. As we do here on Substack. What’s stopping people from teaching courses on Substack right now? What’s stopping “packagers of Substack courses” to create degrees certifying that students have attained a reasonably high level of competence?

Let’s look at some problems with these ideas in the context of existing university structures and see if we can’t overcome them here on Substack. On page 337, Prof. Vedder writes:

Professors would be independent contractors, selling their instructional and research services to the university, which would be the course aggregator and degree certifier. The arrangement between teacher and the university might be such that the amount paid the professor would depend on his or her ability to generate students, moving in the direction of the earlier professorial payment model praised by Adam Smith in the Wealth of Nations. For example, a professor teaching a survey course in psychology might be paid $2000 plus $200 for each student over the fiftieth enrolled who receives a course grade (if the professor generates only twenty students, he or she gets paid $2,000; sixty students nets $4,000; with 150 students, the professor is paid $22,000). To discourage grade inflation (professors trying to attract revenue-producing students through nonrigorous grading), professors could have their pay docked if the average class grade point average exceeds something like 3.0 (a "B" average). Even more sophisticated "grade-adjusted" compensation schemes could be devised.

Okay, so here on Substack we would have teachers collecting fees from students directly. I’m not sure that we would need a payment scheme like the one Vedder suggests above, but it might be nice for a teacher here on Substack to have a guaranteed income from a “school.” In that case, the school could hire teachers as independent contractors, with compensation similar to the one Vedder suggests above. The teacher would receive $2000 minimum, assuming there were at least the required number of students to make it worthwhile to teach the course. Maybe the first time you teach the course, you teach it for a loss?4

These “school-employed teachers” would be better incentivized if paid in proportion to the number and/or quality of students they attracted.

Are there downsides to this? Certainly. We see this on Substack, with some lower quality Substackers attracting more subscribers. But who is to say what low quality is? How can we increase the quality of teaching?

How would we decide on metrics for quality in terms of teaching and learning? Vedder has ideas on this that I can share if you remind me.

Continuing with this same excerpt, Vedder writes:

These schemes are designed to introduce greater competition into the provision of instructional services. Price competition is extremely rare in higher education: How often do you hear a TV commercial from a school boasting "we are 20-percent less expensive than our competitor X," or "register for five courses before August 15 and we will give you an early bird tuition discount 10 percent?" A scheme such as discussed previously should introduce more price competition, and, in the internal university model, provide incentives for professors to take teaching more seriously, moving at least a bit away from the "publish or perish" contemporary environment.

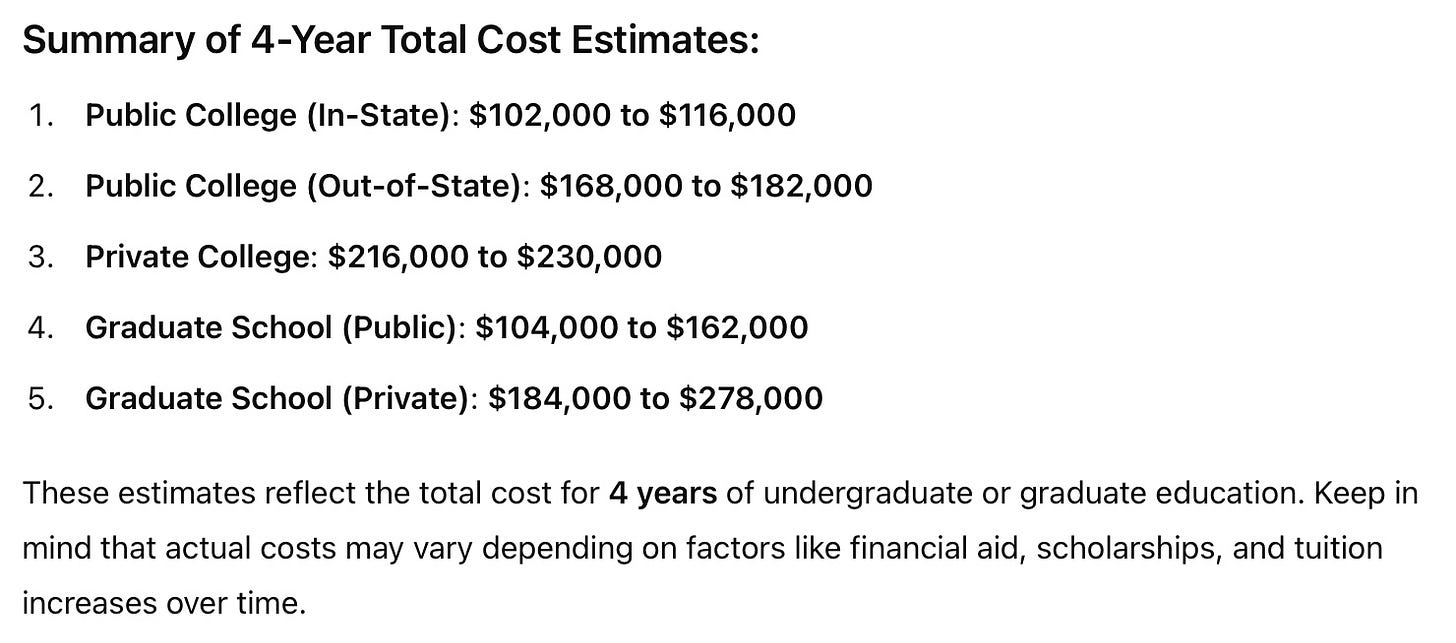

I would certainly welcome some price competition in higher education. How many Americans are excited about the cost of college right now? How much does college costs right now? I asked ChatGPT. Here’s what she said.

Okay, so $100,000 to $300,000. Does this seem accurate? Does college seem worthwhile considering the alternatives? You could take that money and put it down on a house.

By the way, what is the purpose of college? Or a better question, what are your top reasons for attending college or encouraging your kids to attend college?

Let’s continue with this same excerpt from page 337.

This approach to certifying academic competence does not take into account that for many college is much more than just learning and "investing in human capital." Rather it is an act of consumption and socialization, of networking and partying, of drinking and playing sports, as well as studying. Some students—maybe most—might reject the approach outlined above, preferring to take most of their courses in the traditional manner at residential colleges. But even here, there is an opportunity for more competition. Why cannot a student going to Harvard easily with little hassle or extra expense spend a year at Stanford, making two sets of friends instead of one and getting acquainted with two different university cultures? At the minimum, the easing of transfer credit and of doing periods of study at different institutions would seem educationally beneficial—and introduce a bit more competition into traditional education. Why doesn't the Ivy League and top flight other private schools like Stanford, MIT, Chicago, Northwestern, Duke, Vanderbilt, Notre Dame, Emory, and Cal Tech form a consortium where students can pay tuition to their home school but freely attend any one of the schools, perhaps with a provision limiting the number of credits taken away from the home institution where the student takes the largest proportion of his or her academic credits.

So, for some, college is more than just a place to gain skills. College is also for enjoyment, socialization and networking. In my post, “How to Choose a College”, I say that some of the best reasons to go to college are to meet people, make friends, and find a spouse. In that case, I suggest looking at the viewpoint ratio: the ratio of progressive to conservative students. A skewed ratio can screw up your college experience.

With respect to these reasons for going to college, Vedder comes up with some creative ideas. He suggests forming “a consortium where students can pay tuition to their home school but freely attend any one of the schools” in the consortium. Get into UC Berkeley and also attend Stanford, Duke and Harvard. I would sign up for that! This would allow you to meet many more people than just attending one school for four years.

But how can we make this a reality?

Obviously Substack lacks an in-person component. How can we create more in-person learning and social opportunities for Substackers? Or how can we get closer to in-person activities using Substack? One option is to simply call people up. Have conservations over telephone, over email, and over video conference. Then, take the next step of meeting in person. Rent a large room at Residence Inn, my favorite hotel. Their rooms fit five people and come with full kitchens. Or rent an AirBnB or VRBO. Plan to meet for the weekend, a week, or maybe a few weeks if you can afford it. In addition to giving talks and holding discussions, include fun activities like volleyball, hiking, sailing, and visiting museums. Or drinking and pot smoking? At the end, you could take a test to certify your understanding or lack thereof if your parents are paying for it.

Why are the incentives in higher education currently not aligned in favor of students? Vedder has a lot to say about this. I certainly can’t summarize it in one post, but here’s one piece of the puzzle to pique your interest.

Who besides the professors benefit from endowments? On page 137, Vedder writes:

I think Adam Smith was not completely misguided when he claimed endowments led to professors giving up even the pretense of serious teaching.

But the biggest gainers from high endowments may be the endowment managers. Professor Victor Fleischer asks, "Who do you think received more cash from Yale's endowment last year: Yale students, or the private equity fund managers hired to invest the university's money?... It's not even close.” Fleischer says private equity managers received more in payments from managing endowments than students did in the form of financial aid at Yale, Harvard, the University of Texas, Stanford, and Princeton. I have verified that multimillion dollar compensation payments to top endowment managers are not uncommon.

Take another look at those tuition numbers from ChatGPT and ask yourself if it seems plausible that someone is making a lot of money from higher education. Unpacking all of this takes time. This will take multiple posts.

Let’s finish this post off with a vision for what we want. We want higher education to work better for families. We want higher education to look more like the rest of the economy. For example,

Who is to control American higher education? The federal government?….Moving back to a consumer-funded model—where much of the cost of higher education is paid for by its beneficiaries removes much of the rationale for outside oversight. It is a model that closely resembles the model used to produce and distribute most of the goods and services used in America, a model that has produced the economically largest and most productive society the world has ever seen.

That was from page 28. How do we get to a consumer-funded model for higher education? And why haven’t we been talking about this consumer-funded model very much? Or have we? These ideas have been around since the time of Adam Smith and presumably before him.

Let’s finish by looking exactly at Smith’s words in more detail. On page 130-131 Vedder writes:

Arguments Against Endowments

The founder of modern economics, Adam Smith, believed that university endowments had pernicious effects on academic life. Smith asked several questions:

Have those...endowments contributed in general to promote the end of their institution? Have they contributed to encourage the diligence, and to improve the abilities of the teachers? Have they directed the course of education towards objects more useful, both to the individual and to the public, than those to which it would naturally have gone of its own accord?

The one-word executive summary of Smith's answer to all of these questions is "no." Smith asserts that the positive attributes that endowments are supposed to have achieved had not been achieved, at least as of 1776 when he was writing.

If endowments are generous, income from the funds makes the need for tuition fees to pay professors less pressing. While that may make college "more affordable" to students, Smith would argue there are unintended consequences:

The endowments of schools and colleges have necessarily diminished...the necessity of application in the teachers. Their subsistence, so far as it arises from their salaries, is evidently derived from a fund altogether independent of their success and reputation in their particular professions....In the university of Oxford, the greater part of the public professors have for these many years, given up altogether the pretense of teaching.

Smith's concern about endowments were echoed by other pioneering classical economists, notably John Stuart Mill and by scholars in the classical liberal tradition, notably Edwin West.

In a world without endowments or government subsidies, the professors derive their income directly from the students. The better the professor is, the more students will study with him or her and the higher the fee the professor could charge for services provided. Professorial income is directly related to instructional popularity, which in turn is presumably highly positively correlated with competence and excellence. Endowments reduce the incentives for professors to strive to meet their student needs. Thus, modern-day professors lecture sometimes about obscure esoteric trivia on which they did doctoral research and ignore important themes that are fundamental and enduring, as endowments and other public subsidies shield them from competing directly for students in the marketplace. They simply teach less than previously and write obscure papers for the Journal of Last Resort or its equivalent, journals that hardly anyone, even scholars, read. Endowments reduce the role of markets in educational performance and thereby encourage inefficiency.

I have witnessed Smith's point firsthand, as I once taught in the summers at the Economics Institute at the University of Colorado, which was almost entirely dependent on tuition revenues for its financing. Professors were hired not by the year, but by the term, and their long-term compensation and employment were tied to their classroom performance and enrollments. The quality of teaching was exceptional—unprepared or uninspiring professors lasted but one term.

But Smith goes even further: "The discipline of colleges and universities is in general contrived, not for the benefit of the students, but for the interest, or more properly speaking, for the ease of the masters." This anticipates some modern thinking drawing on the economics of property rights and public choice, such as the work of the late Henry Manne and scholars like James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock. It can be argued that so-called not-for-profit universities are in some meaningful sense deriving "profits" (surpluses of funds) that are used to pay the equivalent of "dividends" to the "masters" (powerful teachers and administrators) who in effect largely "own" the university, formal legal documents stating that the governing board owns the institution notwithstanding. Endowments conceivably provide funds that the faculty and administration capture in economic rents, and the students fail to benefit. If true, favorable tax treatment for endowments becomes indefensible, and taxing them is perhaps even desirable, since those funds largely support nontransparent income payments to a small segment of society at the expense of the general taxpayer.

Folks, is it true that we’re being played by the “masters?” The powerful teachers and administrators who in effect largely “own” the university?

Who owns America’s universities? And are they serving you well?

Adam Smith is favorite economist and philosopher.

I won’t include the footnotes for these excerpts. For those you should buy the book.

Now, don’t expect university professors or university administrators to all of a sudden say, “What a great idea!” No, no. If you think this is a good idea, consider doing something about it. Those with the cushy jobs will remain largely silent.

Is Rob Henderson already doing something like this? Is Dan Williams working his way toward this?

They are many good non-profits that get all their operating revenue from “endowments”and government grants. I don’t think the problem with higher learning is competition or the indirect financial incentives, I think it is a failure of mission. For too long higher learning has had a mission disconnected from the economic outcomes of its students. This is what needs to change. The mission should be preparing every student for their next step in achieving an economic self-sufficient life. There should be no acceptable rarified air of academic achievement that does not connect with economic outcomes. Today the industry cranks out hundreds of thousands of indebted graduates with limited skills needed to join the workforce. Higher learning should also have a mission of helping students and faculty launch private enterprise from its various labs.